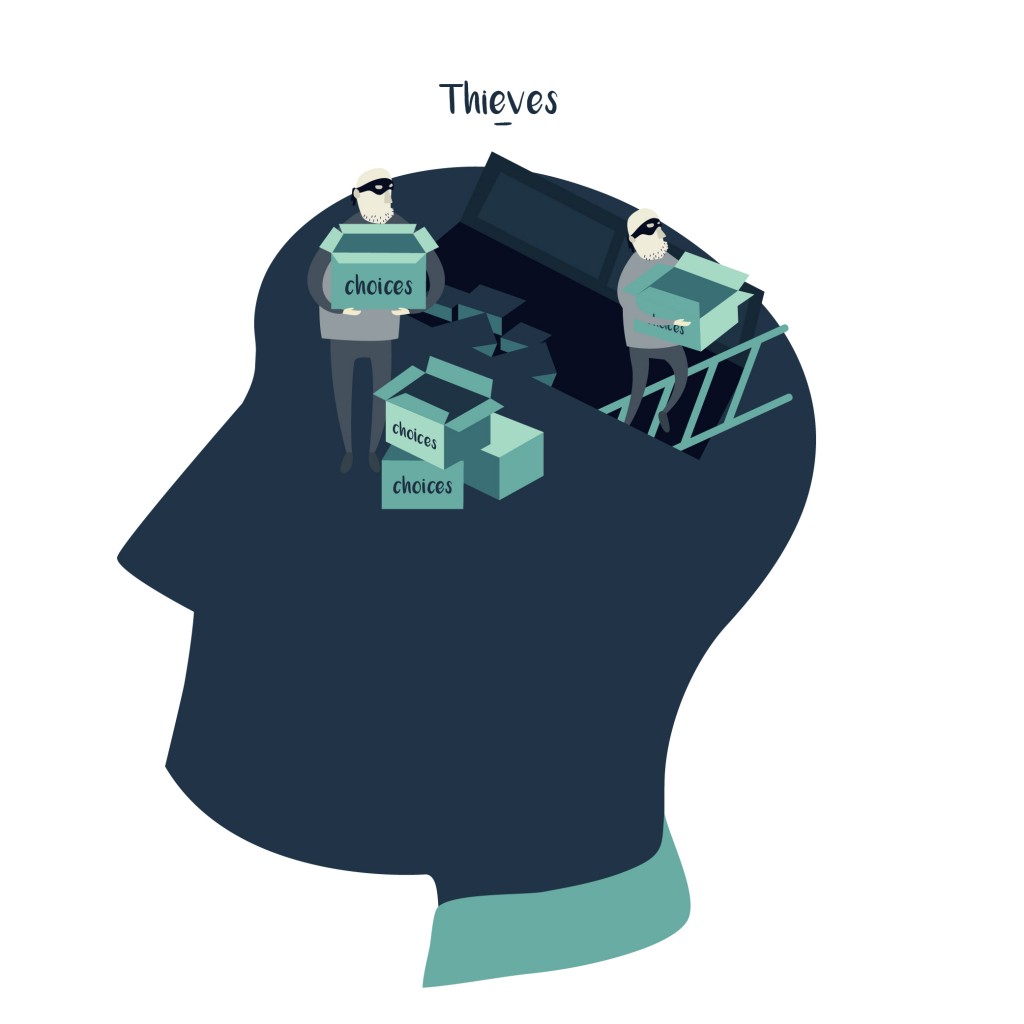

1) An effort to deprive human beings of knowledge so that they cannot see what choices are available to them.

2) A tactic used to prevent people from making decisions based on the facts or in their best interests because the facts are withheld from them, cast in doubt or buried in lies.

3) An effort by an entity or company to mislead or confuse the public about the consequences of the company’s actions in order to destroy any resistance to those actions.

4) A ploy by a company or entity to conceal harm or risks imposed on the public or to ecosystems; a way to increase informational asymmetries between the company and the public.

For example, cigarette makers were aware for decades of the dangers of smoking but claimed in public that smoking was safe. This disinformation distorted public policy in order to guard their profits.

Another example is the actions of Exxon. Exxon, whose own scientists warned as early as 1989 of the catastrophic consequences of increased CO2 levels and greenhouse gases (caused by the burning of fossil fuels), funds organizations that run campaigns of disinformation whose purpose is to sew doubt in the public’s mind about the existence or dangers of the warming of the planet. Doubt in the public about the dangers of greenhouse gases has delayed action against this threat.

One report showed that Exxon gave, despite knowing the dangers of climate change, almost $16 million from 1998 to 2005 to organizations who sought to discredit the scientific evidence related to climate change and convince the public that climate change was a hoax. Exxon also spends (if the company’s 2010 expenditure is typical) between $100 million and $300 million a year in advertising. Media companies are the beneficiaries of much of this expenditure.

See also risk asymmetry, institutional pathology and media.